Silent Night, Peaceful Night

“But now, for the first time, I see you are a man like me. I thought of your hand-grenades, of your bayonet, of your rifle; now I see your wife and your face and our fellowship. . . Forgive me, comrade; how could you be my enemy? ”

THE WESTERN FRONT — DEC. 24, 1914 — The rains stopped and the cold descended, leaving a gauzy mist across the trenches and the No Man’s Land between. But what struck so many soldiers was the quiet.

The guns had first roared that August, guns so loud they could be heard across the English Channel, guns that had already claimed a half million lives. Yet tonight, Christmas Eve, was still. Across the front that snaked from Belgium south through France, only a few shots were fired. This was the most silent of silent nights. Until. . .

“English soldier! English solider!” The call came from a German trench. “Merry Christmas!”

Further down the front, the scene was repeated. “The Boches waved a white flag and shouted 'Kamarades, Kamarades, rendez-vous'.” Then hundreds of soldiers mired in trenches filled with Christmas trees and other gifts from home began to sing.

“Stille Nacht” in German, “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen” from the Brits, “Joyeux Noel” in French. And before any officer could protest or any order be given, men rose and walked, unarmed, towards each other. . .

The Christmas Truce is often thought the stuff of legend. In the 1980s, when John McCutcheon’s song “Christmas in the Trenches” drew ancient World War I vets to his concerts, one told him, “All our lives, our families, our friends told us we were crazy. Couldn’t possibly have happened.” But they had been “over there,” on that night, that silent night.

Truces are as old as war itself. Even in this monstrous war, a shared “live and let live” ideal had stopped the firing long enough to bury the dead, to rest for another day. But as the first Christmas of “the Great War” approached, the Powers that Be discouraged any talk of truce.

When Pope Benedict XV called for a Christmas ceasefire, leaders on all sides rejected the idea. Officers reminded enlisted men of rules against “fraternization.” French Lieutenant Charles de Gaulle regretted such “lamentable” sentiments. Corporal Adolf Hitler, invited to cross Niemansland to meet the enemy, said “such a thing should not happen in wartime.”

Yet by midnight, along several hundred miles of bombed out, burned out wasteland, some 100,000 soldiers had declared their own truce.

Near the French village of Fromelles, British soldiers met Germans. After burying a hundred dead, they shared prayers and the 23rd Psalm. Elsewhere, soldiers roasted a pig. One German knelt while a Brit cut his hair. Men sliced buttons off their coats and traded them, along with hats, cigarettes, and whiskey.

On into Christmas morning, the miracle continued. Soccer games stumbled on icy ground, the goalposts marked by soldiers’ caps. Scottish soldiers played in kilts, and “us Germans really roared when a gust of wind revealed that the Scots wore no drawers under their kilts—and hooted and whistled every time they caught an impudent glimpse of one posterior belonging to one of ‘yesterday’s enemies.’”

Few could believe that it was happening.

“Dear Mother,” one British private wrote home. “Yesterday the British & Germans met & shook hands in the Ground between the trenches, & exchanged souvenirs, & shook hands. Yes, all day Xmas day, & as I write. Marvellous, isn't it?”

“We ended up with ‘Auld Lang Syne,” a British captain wrote, “which we all, English, Scots, Irish, Prussians, Württenbergers, etc, joined in. It was absolutely astounding, and if I had seen it on a cinematograph film I should have sworn that it was faked.”

At dusk on Christmas day, a day of peace on earth, good will toward each other, soldiers trudged back to the trenches. One British sniper recalled his new friend, a German artilleryman, saying, “Today we have peace. Tomorrow, you fight for your country, I fight for mine. Good luck.”

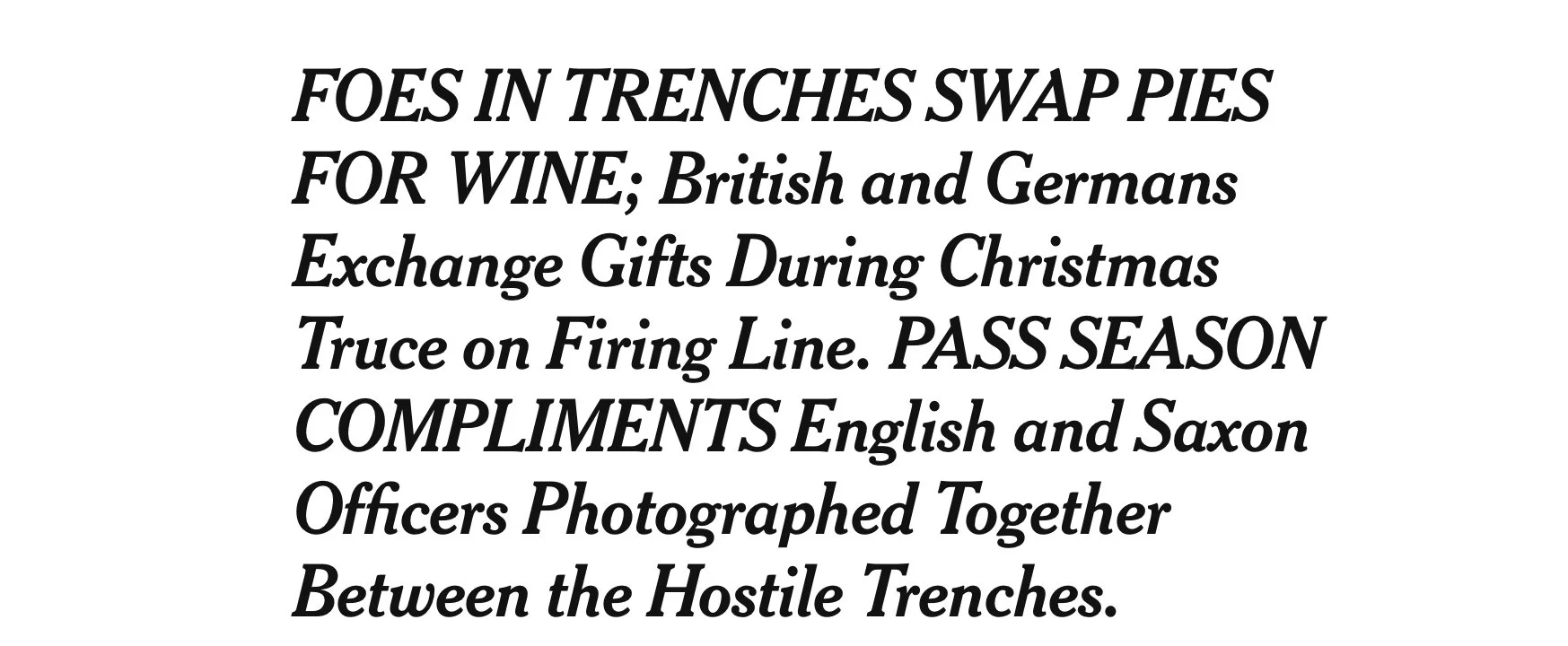

When the guns roared again, the truce came to seem less miraculous than ill-advised. For a full week, despite reports from the front, newspapers said nothing about it. Finally the New York Times printed a short Page 3 article on the “abundance of fun in the sloppy trenches.” British papers soon ran front-page photos of enemies sharing No Man’s Land. And the war went on.

In December 1915, there was talk of another truce but another two million casualties left no one in the mood. No more truces broke the slaughter, leaving the 1914 Christmas Truce as a moment frozen in time, a moment, as the Washington Post wrote on the 90th anniversary, of a “spontaneous, unled cry for sanity.“

The truce has been remembered in songs by everyone from Paul McCartney to Garth Brooks. In 2004, Belgian and German soccer teams played on Christmas Eve to remember the truce and raise funds for a monument. The following year, the French movie “Joyeux Noel” spread the story. That same year, the last man who remembered that silent night died at age 109.

Cynics might scoff. Sure, they laid down their arms, but the next day the slaughter resumed. Even in December 1914, the New Republic had written, “If men must hate, it is perhaps just as well that they make no Christmas truce.” But that night endures as a flicker of hope in a war-torn world. What if. . .

A dozen years after “The Great War” ended, a British veteran, by then a member of Parliament, answered the cynics. "The fact is that we did it,” Murdoch M. Wood said, “and I then came to the conclusion that I have held very firmly ever since, that if we had been left to ourselves there would never have been another shot fired."