The Travels of Ibn Battuta

TANGIER, MOROCCO, JUNE 1325 — Seven hundred years ago, a lone man in flowing robes and turban mounted a donkey and headed east.

“I set out alone, having neither fellow-traveler in whose companionship I might find cheer, nor caravan whose part I might join, but swayed by an overmastering impulse within me and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries.”

Mention early wanderers and the West thinks of Marco Polo. But the legendary Italian was a stay-at-home compared with ibn Battuta.

Having set out for Mecca, Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battuta just kept going. And going. In 30 years of wandering he logged 73,000 miles (compared to Marco Polo’s 15K). He crossed 40 of today’s countries and, as was said in more perilous times, “lived to tell the tale.”

“This is a record of travel which is rare enough today with our many conveniences,” India’s prime minister Nehru said. “In any event, ibn Battuta must be amongst the great travelers of all time."

Travel today is such a pain. Cramped airplanes. Long layovers. But the travels of ibn Battuta, replete with shipwrecks, camel caravans, sultans, and sheiks, still call to the vagabonds among us. يلا حبيبي Yalla habibi. (Let’s go, dears).

Born in Tangier in 1304, ibn Battuta grew up in a family of Islamic scholars. Other than his Berber heritage, little is known about his childhood. Though his studies included the cutting edge science of the Islamic Golden Age, only sheer grit and world class wanderlust prepared him — at 21 — to roam the Medieval world.

Along Africa’s rugged northern coast, ibn Battuta slogged on. It took him months to cross modern Algeria and reach Tunis. There he learned what devout vagabonds soon realize — the value of stopping for a while. After staying two months, marrying, then quarreling with his bride’s family, ibn Battuta hit the road again.

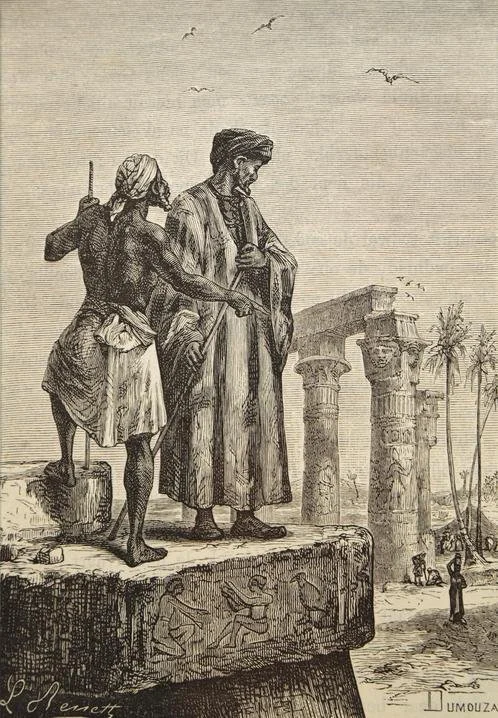

Moving east, always east, he crossed modern Libya. By the next spring, he reached Alexandria. The fabled lighthouse, wonder of the ancient world, was in ruins but ibn Battuta was more impressed by “a learned and pious imam.”

“I perceive that you are fond of traveling into various countries,” the imam said. “You must visit my brother in India.” And another brother in China, “and when you see them, present my compliments.”

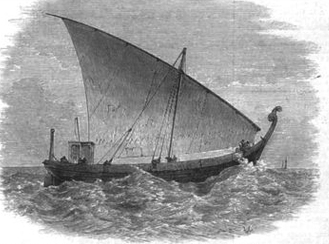

Though still bound solely for Mecca, ibn Battuta began to dream. India! China! By the time he reached Cairo, “peerless in beauty and spendor,” the whole world had become his mecca. And after completing his hajj, he caught a dhow on the Red Sea coast and sailed towards the Horn of Africa.

At this point, it’s easier to track ibn Batutta on a map. Look:

After hopscotching the African coast, he headed back across the Arabian Peninsula, north into Anatolia, then across the Black Sea and the steppes of Central Asia, almost to Moscow. But no map can capture the rigors of travel centuries before the first guidebooks and language dictionaries, the first Rick Steves or Air Bnb.

Ibn Battuta survived blistering deserts and nights so cold he had to wear “three fur coats and two pairs of trousers . . . Boots of bearskin lined with horseskin. . . “ When fever struck, he tied himself to his donkey’s saddle. But cities, with their thieves and mobs, proved even more perilous.

Damascus. Constantinople. Samarkand. Isfahan . . . He was astounded at their sprawl. Of one Turkish city he wrote, “It shakes under the weight of its population, by reasons of their multitude, and is agitated by them in a manner resembling the waves of the sea.” Riding horseback, he pressed on through the hordes until human density stopped him. He sat on his horse for hours.

Moving south across the steppes, he saw cities ravaged by Mongol hordes, and met rulers and holy men fascinated by his travels. He continued across the Hindu Kush and into Iran. Finally reaching India, he was appointed a judge in Delhi. He stayed for months before boarding a ship bound for China.

Shipwrecked, he almost drowned. He moved on only to be robbed. Pirates. Bandits. Scholars today are unsure whether he reached China, but he described China’s unique paper currency and a great “obstruction,” which some think might have been the Great Wall.

By the time he headed home, ibn Battuta’s pilgrimage had stretched to 21 years. Deciding to head again to Mecca, he sailed on monsoon winds to modern Yemen, then trekked north along the Persian Gulf through Baghdad and into Damascus. But in 1348, the Black Plague was spreading death across the Mediterranean. He saw piles of corpses, whole towns empty, dying.

When ibn Battuta finally came home to Tangier, his found his home empty, his parents long gone. And travel, he discovered, “gives you home in a thousand strange places, then leaves you a stranger in your own land.” He stayed three days, then headed south.

This final journey took him across the thriving desert empire of Mali. He visited the fabled Timbuktu, saw hippos and slaves and women — unveiled! — of “surpassing beauty.” He might have gone farther but the Sultan of Morocco somehow got a message to him, calling him home.

Back in Tangier, ibn Battuta followed the sultan’s advice. He dictated accounts of his wandering. Travel, he discovered, “leaves you speechless, then turns you into a storyteller.”

A Gift to Those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling soon amazed the Arab world. Finally brought to Europe in the 1800s, The Travels of ibn Battuta became the most complete account of a world lost to time.

For the rest of his life, the globetrotter stayed home. After a decade as a judge, ibn Battuta died peacefully in bed.

Today, Tangier hosts flights from around the world. Travelers, complaining of jetlag and missed connections, shuffle through the Ibn Battouta Airport. Those from the Arab world know the name. Those from elsewhere just shrug.

“When’s our flight?”

“I am so ready to be home.”

“Would it kill them to give us a meal this time?”