How the World Saved the Planet

EARTH — 1960s — Pssst. Pssssssssssst. Throughout the countries of convenience, aerosol spray cans are everywhere. Deodorant. Paint. Hair spray. Cleaners, air fresheners, insect repellents. . . Meanwhile, each and every refrigerator is not just cooling food. It is, we will soon learn, opening a hole in the ozone layer.

Last Tuesday, September 16, another World Ozone Day came and went. Chances are good that you did not celebrate. Ozone? The name rings a bell but most have forgotten the term, the danger, and how the entire world collaborated in the name of science.

“In our long history,” said Britain’s David Attenborough, “there is one unprecedented act of humanity in which every country on earth came together to protect the future of life.”

Among the many environmental threats of the 1960s — smog, DDT, rivers catching fire — ozone didn’t make the cut. Oblivious to the O3 in our atmosphere that blocks UV rays and saves us from blindness and skin cancer, we just kept spraying. And cooling. And finding other culprits for early signs of ozone depletion.

Many blamed air travel. Jets flying at 37,000 feet must be leaving trails that thinned the atmosphere. New supersonic jets were banned from the US. The ozone layer got thinner. Perhaps fertilizers were the cause? Or methane from cow flatulation? The Pentagon admitted that nuclear war would do a number on the ozone but that hadn’t happened — yet. Then a biochemist in Southern California saw the sunlight.

In 1974, Frank Sherwood Rowland (above left) published his findings in Nature. Man-made compound gases called chlorofluorcarbons (CFCs) were rising into the atmosphere, mixing with sunlight, and turning the sunblocking O3 into the porous O2. “I knew that such a molecule could not remain inert in the atmosphere forever,” Rowland said, “if only because solar photochemistry at high altitudes would break it down."

The usual Merchants of Doubt leapt into action. CFCs were in every freezer, every aerosol can, every chemical company’s profit sheet. “All we have are assumptions,” said a spokesman for the Aerosol Education Council. “Without experimental evidence, it would be an injustice if a few claims — which even the critics agree are hypotheses — were to be the basis of regulatory or consumer reaction.” One British scientist described the danger of aerosols as “utter nonsense.”

As the fate of the planet would have it, an emboldened environmental movement was in full swing. In 1975, the Food and Drug Administration recommended studying aerosols. A NASA satellite measured the ozone layer and confirmed its breakdown at higher levels. Then governments (gasp!) got busy.

Oregon banned aerosols in 1975. Michigan followed the next year. The EPA urged a full ban and in 1977, required a warning label on all spray cans. And people, who were less confused and angry in those distant days, responded. By 1978, sales of aerosol sprays had dropped 50 percent.

But sprays, we soon learned, were not the only culprit. Even as the new Reagan administration was weakening the EPA, science revealed that coolants in refrigerators were wreaking the same havoc on the ozone. That’s when the world took notice.

In March 1985, delegates from 43 countries met at the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer. Though no bans were issued, Vienna set up guidelines, research panels, and the startling precedent of a world coming together to save itself. But it took more science, and more alarm, to silence the last doubters.

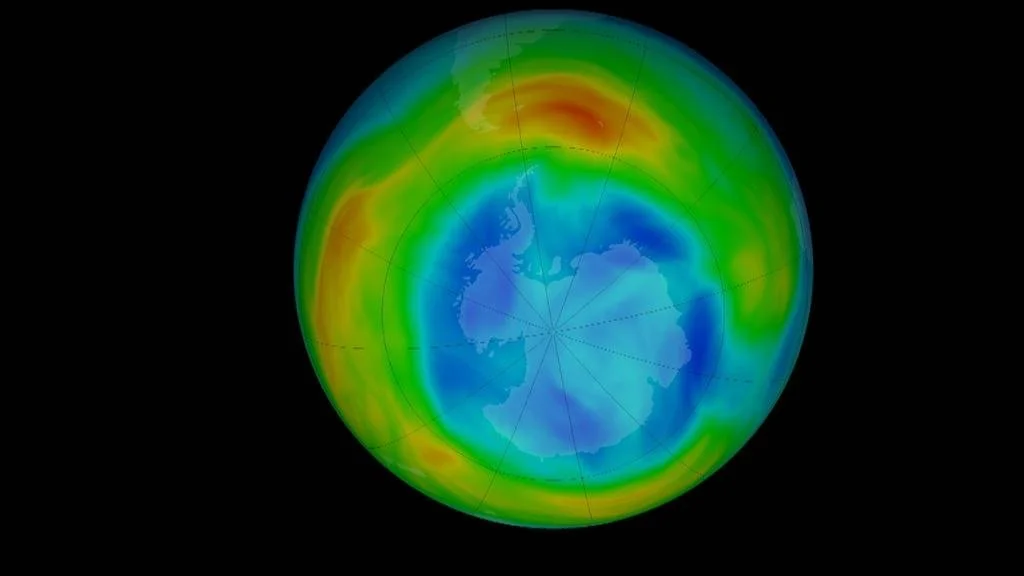

Two months after the Vienna conference, Nature published another study on ozone. This was no mere “hypothesis.” Three British scientists had measured ozone levels over Antarctica. What they found was a hole. A hole in the ozone, enormous and getting bigger. The shockwave circled the planet.

In 1986, the EPA warned that, over the next several decades, further ozone depletion would lead to 40 million skin cancers and 800,000 deaths. Even the Merchants of Doubt were convinced. DuPont, which had initially rejected the “utter nonsense,” backed strong action and began researching alternatives to CFCs. The stage was set for Montreal.

Meeting in the summer of 1987, delegates from 43 countries froze CFC production at current levels and agreed to cut production in half by 1999. But even that, scientists warned, would not be enough. So another conference, in London in 1990, banned all CFCs by century’s end. Two years later, the deadline was moved up four years.

Alternatives to CFCs soon came out of the lab and into our cans and freezers. It was, David Attenborough said, “the greatest planetary repair job ever attempted.” And it worked.

By 1995, the ozone hole had stopped expanding. The repair has continued ever since, steadily shrinking the hole, which is expected to reach pre-aerosol levels within a few decades. Some two million annual skin cancers never happened. Between a half and a full degree (Celsius) of global waring was avoided.

By 2008, every country in the world had signed the Montreal protocol. Frank Rowland won a Nobel prize and just about every other award you can get for saving the planet. And this year, the same planet that once made “ozone depletion” an urgent threat, ignored World Ozone Day.

A follow-up to Montreal, the Kigali Amendment passed in 2016, is attempting to phase out HFCs, which contribute to global warming. How’s that working out? Not as easy, it seems, because the Merchants of Doubt are working overtime and the people are angry and confused. There must be a lesson here — somewhere.

Last week on World Ozone Day, the UN Secretary General recalled the “repair job” of the ozone layer. “This achievement reminds us that when nations heed the warnings of science, progress is possible.”

Wow! Science. Cooperation. Progress. What a roadmap!