How Rumi Spread His Joy

CENTRAL TURKEY — NOVEMBER 1244 — Mongols on horseback are sweeping across the steppes of Asia, pillaging, purging. Much of Persia has fallen. Turkey lies in their path.

Then one afternoon, within the walled streets of Konya, a popular imam in a turban rides a mule, trailing followers behind him. A ragtag man stops the mule and the two men begin talking. When the imam comes down to earth, the world is gifted with a new and timeless voice.

Before Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī and his “doorway to the sun” met that day, the imam was “bored with myself. . . For forty years my mind drowned me in thought,” Rumi later wrote. But when he met Shams el-Tabrizi. . .

I shed my trickster’s skin

Silence! No more details

I had enough of my own fever —

I leapt free.

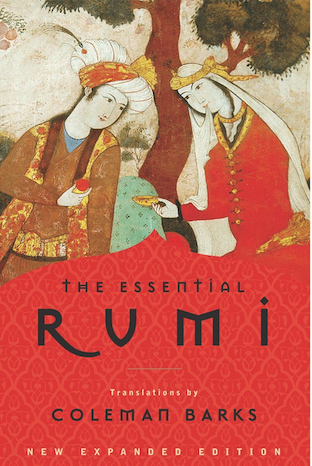

As his muse was for Rumi, so Rumi is for millions today. Simplified as “the poet of Love,” this Sufi mystic is a euphoric Walt Whitman for the whole world. “His poems have never been for me, or for most readers, museum curios from the thirteenth century,” wrote Coleman Barks, editor of the best-selling The Essential Rumi. “They are food and drink, nourishment for the part that is hungry for what they give. Call it soul.”

With an uncanny skill for cutting through life’s clutter, Rumi is now the “go to” poet for that ever-expanding group of the world weary. Listen:

Take the cotton

Of the mind’s doom-ridden chatter

Out of your ears.

Hear the booming voice of the heavens

The roar of fate

The ruckus the muse makes.

Rejecting despair, renouncing the self and all its sorrows, Rumi calls across the centuries for celebration.

Out beyond the fields of wrongdoing and rightdoing

There is a field. I’ll meet you there.

But who was this singular voice that defies time and troubles? Ask him:

I am the black cloud in the night of grief who

Gladdened the day of festival.

I am the amazing earth who out of the fire of love

Filled with air the brain of the sky.

Yet if you must know, Rumi was born in a small village in what is now Afghanistan. His father, also an imam, filled him with verses from the Qu’ran and comforted the boy when, at age five, he began to see angels. “These are angels from the unseen world. They are showing themselves to you to offer their favors.”

But the family soon saw devils, Mongols coming to conquer. Fleeing west, Rumi and his family lived for years in Samarkand, then fled to central Turkey. There Rumi succeeded his father as a popular imam whose talks drew hordes of listeners.

He might have stayed local, bored with himself, but for the chance encounter with his muse. Shams el-Tabrizi was an outcast among Muslims. Calling out for joy in lieu of ritual and recitation, Shams had roamed the Islamic world for decades. More than twenty years older than Rumi, Shams was the “someone with a deep thirst,” the imam had been seeking. Whenever Rumi began reciting the Qu’ran, Shams stopped him.

“Where’s your own voice? Answer me in your own voice!”

Their friendship lasted just two years before Shams disappeared. Wandered off? Murdered? No one knows, but Rumi had already begun to spin out couplets and quatrains dedicated to love, life, and love of life.

Be a fool, drunk on love, soaked in awe

Till dry weeds are sweet as sugarcane

A lion leaps out of his cage

A man leaps out of his mind

Bravery is delicious madness.

“Spin” here is no metaphor. Shams was a dervish, member of a small Sufi sect known for seeking ecstasy through wild dances, often twirling and twirling. Rumi soon began spinning as he improvised his poems, becoming “the river of countless messages.”

The mind is a caravanserai

Each morning new guests arrive. . .

All thoughts, happy or sad,

Are guests. Welcome them.

Rumi never preached again. Instead, he devoted the rest of his life to poetry. He wrote only two books, one a collection of praise to Shams, the other a sprawling compilation of “spiritual couplets.”

Still composing on his death bed, he died in 1274 at the age of 66. His funeral procession filled the streets of Konya with mourners and celebrants of all faiths. Only the celebrants had absorbed his message.

When I leave this world, don’t say I died

Say I was dead, then came to life

Say the Beloved whisked me away.

Though increasingly popular throughout the Persian and Arab worlds, Rumi remained unknown in the West until translated in the 18th century. Then his timeless couplets spoke to fellow mystics ranging from Emerson to Schubert. But it took a modern poet to open the door for the rest of us.

Sometime in the mid-1970s, Robert Bly handed a dry, scholarly translation to a young poet. “These poems need to be released from their cages,” Bly told Coleman Barks. Reading, marveling, Barks felt like he’d found a friend, “one we do not know and have never met, yet who is deeply familiar. Heartbroken, wandering, wordless, lost, and ecstatic for no reason.” Working with a translator, Barks compiled The Essential Rumi. When it came out in 1994, Time called Rumi “the best-selling poet in America.” Better translations have since emerged, enhancing the 21st century allure of a 13th century mystic.

“Rumi resonates today,” one translator said, “because people are thinking post-religion. He came to see mysticism as the divine origin of every religion.”

Back in Central Turkey, a tall turquoise spire still stands above several domes marking Rumi’s tomb. Five thousand people visit each day, some sobbing, others praying or reciting favorite passages.

Leaping free of dogma and despair, Rumi has transcended time and touched the whole world. Somehow, it seems, he always knew he would, given his muse.

Love you strung my heart with gold

What else can I do but sing?